Bridget Crocker on Rowing with Her Friend Doreen

Sometimes a woman has to paddle against the current.

When I’d first met Doreen, last season, she was a highsider – a porter and training guide who helped weight the rafts through the Zambezi’s high-volume hydraulics. She was barely five feet tall and less than a hundred pounds, but as a highsider, Doreen carried heavy coolers, oars, and rafts in and out of the steep Batoka gorge, matching the men load for load. The other highsiders, all male, started complaining that she was taking more than her share, making it harder for them to provide for their families. Doreen didn’t have a family of her own, they argued, so she didn’t need the money like they did.

It was decided that Doreen must quit being a highsider and become the manager’s “house girl” – and so she came to work for us, doing the washing, ironing, and floor polishing.

Above: Bridget Crocker and crew take on Rapid #8 (aka Midnight Diner). Zambezi River, Zambia. Photo: Greg Findley/Detour Destinations

Doreen joined our groundskeeper, Gabriel, and guard, Mr. Amos, bringing our total number of staff to three.

“You have to do something about them,” I’d told Greg. “I don’t want to be the Madam – it makes me uncomfortable to have them doing all the work.”

Back home, I had cleaned plenty of motel rooms for money in-between river guiding seasons. To me, having servants was an affront to my working-class ethos and Aquarian sense of global equality.

“What do you want me to do?” Greg responded. “Throw them out? Then they won’t have jobs.”

Obviously, that wouldn’t do. “Fine, then,” I proclaimed. “But I’m not going to monitor the ironing or oversee afternoon tea.”

As it turned out, Doreen and I had a few things in common, besides scrubbing toilets for cash. We were both twenty-one years old and had grown up next to rivers: me in a small town next to Wyoming’s Snake River and Doreen in a Tonga village outside Choma, near the upper Zambezi. Before meeting us, she’d never been around mazungus – white people – in her life. Before coming to Africa, I had never been around black people in my life.

Young Bridget Crocker at home on Wyoming’s Snake River. Photo: Marilyn Olsen

Doreen Hamangaba – highsider, housekeeper, kwassa kwassa queen. Livingstone, Zambia. Photo: Bridget Crocker

We became best friends, spending afternoons swapping dance moves while playing UB40’s “Red, Red Wine” over and over. We eventually broke the cassette tape, so Doreen brought in her tapes from home of Zairian kwassa kwassa and Lucky Dube, a South African reggae megastar.

“What’s your biggest dream?” I once asked her. “If you could have any job in the world, do anything with your life, what would it be?”

She looked at the floor, and then cautiously up through thickly fringed lashes. “When I was a highsider,” she said, “I was just wanting to take those oars in my own hands.” She smiled earnestly. “I was wanting to steer the boat and be the one who is guiding, as you yourself are. That is my dream.”

***********

My third season in Zambia, I applied for and landed a job guiding on Ethiopia’s Class III Omo River. Of all the rivers in the world, it was the one I most wanted to run, primarily because it was the stomping grounds of LUCY (Australopithecus afarensis), one of the earliest humans. Since the first descent in the early seventies, the Omo had been run sparingly, and only a handful of women guides had ever rafted it.

“Greg will let you go?” Angela was concerned. She relinquished the luxury of pursuing her dreams when she married and had two children.

“Yes, of course,” I said.

Doreen helped me pack, carefully handing me carabiners, pulleys, and my river knife.

“I know you will be careful, my sister,” she said, smiling proudly. “Are you afraid of the rapids?”

“Not so much the rapids,” I said. By now, I had guided Class III and IV rapids in Wyoming, Idaho, and California. “I’m more scared of the hippos and crocs.”

Doreen erupted in a deep, carefree laugh. “Only tell them that I have sent you. They will not harass you then.”

Dropping into Rapid #5 (aka Stairway to Heaven). Photo: Greg Findley/Detour Destinations

Greg drove me to Bulawayo, Zimbabwe, to board a train for Harare, where I was to catch a flight for Addis Ababa. With time to spare before the night train departed, we ducked into a matinee of The Power of One. We came out of the movie misty-eyed from its message of racial equality and being true to oneself, only to find we had been robbed. My bag filled with river gear was missing, as was the guard we had paid to watch our Rover.

We went to the central police station to report the crime. When it was my turn at the counter, I slid my passport over to the officer on duty.

“My duffel bag was stolen from our vehicle,” I began.

“Oho,” he raised his eyebrows and loudly flipped through the stamped pages of my passport. “And tell me, who is speaking for you?”

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“Who is reporting the crime for you? Who is speaking for you?”

“I’m speaking for myself,” I said, bewildered.

“No, no. You must have someone to speak for you – a husband, father, or brother. Otherwise, you cannot report it.”

“Here’s my boyfriend. . .” I offered.

“Sorry. He is not your husband.”

“But, my father and brothers are in the States.”

“Well, that is truly unfortunate, then. It is Zimbabwean law that a woman must have someone speaking for her to report a crime. Next in the queue,” he handed back my passport, looking over my shoulder, no longer seeing me.

Stripped of my river armor – life jacket, helmet, knife, throw bag, wrap kit – I felt vulnerable and ill-prepared for guiding a fourteen-day trip on a remote wilderness river near the Sudan border.

“What a bummer,” Greg said, as we took our seats at a neighboring bar. “You were really looking forward to going.”

I was tempted to numb my disappointment with a Cane and Coke, lean my head on Greg’s comfortable shoulder, and head back to Livingstone. I could nearly taste the cocktail’s sugary oblivion. Then I remembered Doreen beaming at me as I left, her compact, sturdy arms waving madly from the gate.

“Oh, I’m still going,” I said, and ordered a Fanta.

“But you don’t even have a lifejacket,” Greg pointed out.

“Yeah, but I’ve got a ticket.”

I boarded the plane as scheduled, bolstering myself with the knowledge that I had been chosen for this – been handed my dream-come-true – and there might never be another chance. I flew to Addis intent on holding those coveted oars, Doreen’s proud smile nudging me forward the entire way.

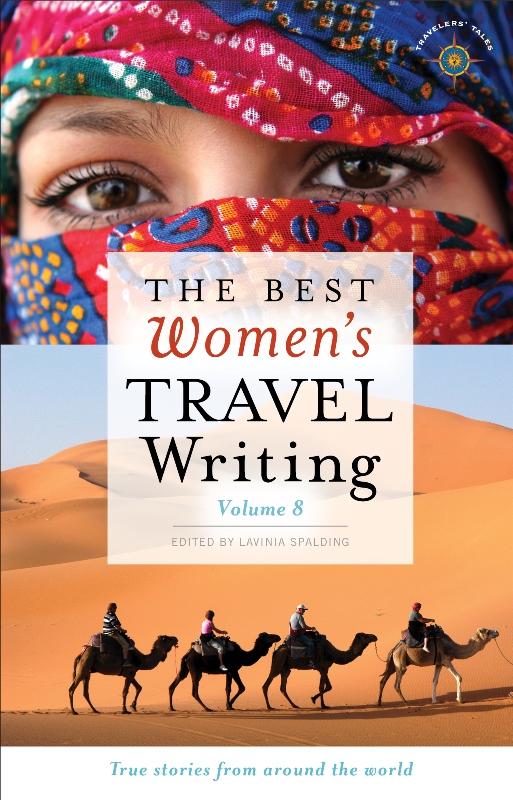

This story first appeared in The Best of Women’s Travel Writing, Volume 8: True Stories from Around the World.